Please read part

one,

two,

three,

four,

five, and

six if you haven't already.

Getting up at midnight to summit a mountain was a surreal experience. It was dark and cold, the wind was howling, metal equipment was jangling, almost everyone else was sleeping, and the only light we saw was the ghostly glow of our headlamps. I felt as if I were on the moon.

Before we set out, our guides informed us they would not bring their backpacks, so they could carry ours if necessary. "Pshaw," I thought, "No way am I inflicting this bag on our guides." Oh, how I would later change my mind and be grateful for their offer.

I started out strong. I had no altitude sickness and I was well dressed for the cold. It was a huge surprise to outpace my brother. While we were hiking, I thought, "Today might be the first time

I beat Andy at something." Throughout our lives, Andy has always crushed me both academically and in feats of physical endurance.

But, surprising to us both, I felt good while Andy was breathing alarmingly heavy and complained his hands were cold. We exchanged gloves and Tumaini took Andy's pack. I had conflicting feelings of sympathy and triumph about this.

This all changed in one horrible moment only 1,000 feet from the summit. All at once, like some cruel joke, my legs turned to rubber and my pack dragged me to the ground. I fell like a puppet with cut strings. Andy stopped hiking and asked in disbelief, "Are you

serious?" It was all hardship for me from that moment forward and Andy only got stronger as I got weaker.

Tom was cold and just wanted to get it done so he raced ahead with Amani while leaving Andy, Tumaini, and I to follow. He made it up first and, as you can see in the photo above, he did it all before the dawn.

Andy took this picture of me as we approached the summit, past Stella's Point, only 300 vertical feet from the peak. You can get a good sense of how cold it was by the amount of clothing I was wearing. For the record - I was wearing fleece pants over my hiking pants, four layers on my upper body and a windproof shell, gloves, wool socks, and a balaclava. We estimated it was around five degrees fahrenheit.

Despite being so close to the summit, I can't tell you how much this part of the trip hurt. I would take ten paces, stop, lean on my trekking poles to catch my breath, and pull myself together for another ten steps. It was agony. At one point, I fell to the ground and had to dig into every energy reserve I had to get back up. It was not glamorous.

The cold added to the unpleasantness but wasn't as big an issue as the altitude. When you are climbing at this elevation, everything in your body wants to give up. It's a huge mental battle. The only thing motivating me was the fact that I had traveled 8,000 miles to get here, and I'd be an idiot if I turned back with only 300 feet to go.

Andy made it to the sign first. The sunrise was blinding, check out our long shadows. I wish we had thought to have the guide take our photo together but we were both not thinking clearly.

Here's the money shot. The moment you've all been waiting for. I wish I could tell you how triumphant I felt, how this shot made it all worth it, and blah blah blah. The truth is, when the big moment finally arrived, I peeled the balaclava off my face, sat down, put on my biggest, fakest smile until the picture was taken. As soon as it was, I stood up and said, "Alright, I'm outta here." This smile, as recorded on film, was the only time I smiled that day.

While I made for the exit as soon as the picture was taken, Andy went to walk around the perimeter of the summit. Kilimanjaro doesn't come to one big point like classic mountains, rather it is like a lopsided tabletop, with Uhuru peak being the highest point, ringing an enormous crater in the center.

We split up. I headed back down and hoped I could find the way back to camp while Andy went with Tumaini to investigate the Ash Pit in the center of the mountain. Andy wanted to one-up everyone who has climbed Kilimanjaro. A good amount of westerners climb Kili every season but very few go to the Ash Pit.

In this photo, you can see one of the boulders behind which Andy took a crap. He had no toilet paper.

Here's the Ash Pit that Andy went through hell to see. It actually was pretty cool. The ash pit was not visible from Uhuru peak, so I didn't see the Ash Pit until Andy had his pictures developed.

After struggling so hard to reach the summit, I had given no thought on keeping any energy in reserve for the descent. I have never felt so utterly drained in all my life. I stumbled the whole way down, with barely enough strength to prevent myself from careening out of control down the path. The ground was made of ash, which allowed hikers to slide down with each step, as if skiing. This would have been fun, had I the strength to do it.

I caught up with Tom and Amani, thankfully, so I had company in my misery. Tom was suffering from a terrific migraine and bolted down the mountain in pursuit of some altitude relief. I was so embarrassed when they would have to stop and wait for me stumbling behind. I kept apologizing for being so slow.

I looked ridiculous. It was the only time I've ever been so fatigued that I could barely walk. It wasn't until later that I realized I hadn't eaten or drank anything in nearly eight hours of strenous exertion. If you are climbing Mount Kilimanjaro, let this serve as a cautionary tale. My two word recommendation: EAT. DRINK.

As we approached camp, we saw people who were in worse shape than ourselves. One woman was being led down on the arm of her guide as if she were blind. I've read about people being carried down on stretchers. Everyone in camp was so beaten and tired, we looked like refugees. The atmosphere was restrained and somber, everyone was too broken and exhausted to celebrate.

Andy was a catastrophic mess when he stumbled into camp a full hour behind us. Dust had gotten into his eyes on the trail, making them an angry shade of red. His lips and face was chapped from the wind. He had snot dripping out of his nose and that combined with his non-wiping bathroom break made him a truly disgusting specimen to behold.

When we were getting ready to descend further, after an hour or so of rest, Andy sat up and howled in pain for a full five seconds. He could say that he saw the Ash Pit but I'm not sure it was worth the physical cost.

After a long uneventful hike down, we made it to our last campground. The next morning Andy took this shot of the triumphant team.

We had read about tipping our guides and porters at the end of a trip and, at breakfast, were unsure how to broach the subject. It wasn't much of an issue because Amani came over to us and said, "We'd like the tip now." It's an awkward experience to hand over money and stand there as a group of recipients are receiving it. Tom, Andy, and I were apprehensive as we wondered, "Did we tip enough?"

We were relieved when the porters broke out into applause and smiles. They formed a line to shake our hands and hug us. Their gratitude took me aback and made me wish I had tipped more. Our porters and guides were some of the most hard-working and gracious people I've ever met. I still smile when I think of that moment.

For general reference: The rule is to tip ten percent of the total cost of your trip. We tipped a little more than that. I later did the math and figured our porters had busted their asses for $6-7 a day. Bring plenty of money, when you see how hard these guys work, you'll wish you could give them more.

Also, a note to prospective Kili hikers, I have read reports of porter abuse where porters are given inadequate gear or been otherwise abused by tour group leaders. I

did not see any examples of this during our time with Good Earth. But please be on the lookout for it and if you see it,

report it.

On the way back to the hotel, we stopped in Moshi for one last lunch with our tour group. The restaurant was of questionable quality but I saw a few Westerners (read: whiteys) eating so I figured it was safe. I ordered the fish with tartar sauce. It tasted a little weird, but I finished it off to be polite.

Big mistake.

Afterwards, on the long drive back, I felt gross. My stomach wasn't right and I was dizzy. When we got back to the hotel, I laid down while Andy and Tom went downtown to take some pictures. Before they left, I asked Andy to send an

email to my wife from the internet cafe.

The need to puke awoke me from my nap. I threw up a total of ten times, four in the first installment and six in the next. I threw up so hard, I feared for my life and cried out for help. None came.

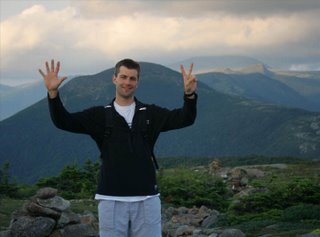

At around the time I was expelling my guts through every orfice of my body, Andy was posing for the picture above in downtown Arusha.

In Andy's defense, he took good care of me when he got back. Also, our flight did not leave until late the next day so I had some time to recover. Unfortunately, I was not sufficiently recovered to join Tom for a celebratory Kilimanjaro beer in the airport terminal.

We were witness to a couple of crafty incidents at the airport. The woman at the airline flight counter charged Andy a $10 "safety fee" when he checked-in. When he came up to us, he asked, "Did you guys get charged a 'safety fee'?" We both laughed and asked what he was talking about. Andy went back to her and asked what it was going on. She, clearly busted, responded, "Oh, it's been waived" and handed him his $10 back. No hard feelings about, you know, trying to rip you off.

Also, there is a very prominent money exchange in the incoming flights terminal and none on the outgoing flights terminal. So it's easy to change your money into schillings and difficult to turn them back into dollars. I am beginning to think this is by deliberate design.

My advice is not to bother exchanging your money for schillings, everyone in Tanzania prefers American dollars anyway. As a result of this trickery, I am still the proud owner of 135,000 Tanzanian schillings. I cannot find an American bank which will exchange the goddamned things.

The overwhelming majority of Tanzanians I met were friendly, hard-working, honest, and kind. But be on the lookout for these shenanigans.

One more thing I discovered about myself on this trip, 25 hours in plane transit makes me go a little crazy. When I landed in Boston, I was completely disoriented. Time seemed like a dimension I had excused myself from for a full day. It took me four days to get over the jet lag.

As trying as it was, I'm happy to say I did it. I made it. I traveled to Africa and climbed Mount Kilimanjaro. The instant I saw the picture above of Andy, I knew it was the one I would use for the closing shot of this saga. Thanks for reading.

If you are planning a hike up Kili, please don't heisitate to

contact me with any questions. I recommend

Good Earth tours for a travel guide, they were excellent and affordable.